Over the past 25 days, Kerala has been reporting daily COVID-19 cases ranging between 10,000 and 15,000, with none dip. Kerala is one among the few states with a high number of COVID-19 cases in India within the past few weeks – on July 8, as many as 13,772 people tested positive for coronavirus. In many other parts of the country, the daily caseload has been steadily declining. Maharashtra, as an example , which has been accounting for the very best COVID-19 cases since the pandemic started, reported 9,083 COVID-19 cases on July 8.

According to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, as of July 8, Maharashtra had the very best number of active COVID-19 cases (1,17,869), followed by Kerala (1,08,400). However, on comparing the previous day’s data, Maharashtra’s total active COVID-19 rose by 333, while Kerala’s active cases rose by 3,823, which is that the highest within the country for that day. it’s also important to notice that in Kerala, the amount of deaths is lower compared to Maharashtra, and therefore the recoveries are high compared to other states.

Incidentally, although Kerala’s daily COVID-19 cases remain high, it’s been plateauing (a period of stability) since mid-June, while other states are witnessing a decline. as an example , between May Day and seven , when COVID-19 infections were at their peak across the country, Karnataka and Kerala recorded a mean 46,045 and 36,239 daily cases respectively. Over the previous couple of days, between June 30 and July 6, Karnataka and Kerala recorded a mean daily case of two ,646 and 12,226 respectively.

Dr Jayaprakash Muliyil, an epidemiologist, explains that the rationale Kerala has had a steadier curve as against a rapid fall and decline might be thanks to two reasons. “One, the amount of undetected COVID-19 cases in Kerala must be lower. And two, it might be because behaviourally, more people are going and getting themselves tested once they have symptoms, instead of hiding it. If most of the people have mild symptoms, they’re going to not get admitted to the hospital, but the case are going to be recorded,” he says.

The sharp rise and decline COVID-19 cases in places like Delhi and Karnataka is due to rapid spread of the virus, then because the amount of individuals infected is more, a threshold immunity is reached. “Simply put – there are fewer people left to infect, which causes a pointy decline. differently to form the amount of cases fall is to enforce a reasonably serious lockdown,” says the epidemiologist.

Health experts say that Kerala was largely ready to contain the sudden spike by slowing down the pandemic’s curve. “While most of the states witnessed a rapid change within the pandemic’s curve within the first wave with a rapid rise and fall, Kerala saw a slow rise in cases,” says Kochi-based rheumatologist Dr Padmanabha Shenoy, who has been analysing COVID-19 data.

Dr Arun NM, a Palakkad-based general medicine expert who has been tracking the COVID-19 data, drew a couple of similarities between the primary and second waves in Kerala and other states. Kerala witnessed the primary wave of high COVID-19 cases only after September 2020, when other states were reporting a decline within the daily infections.

“In the primary wave, Kerala didn’t witness a rapid spike in cases like other states. an equivalent is occurring within the second wave, too. within the first wave, Kerala’s daily COVID-19 cases plateaued out for a couple of months, from around 5,000 to 6,000 cases between November 2020 and January 2021. it’s by March that the daily cases dipped to the range of two ,000,” explains Dr Arun.

Dr Shenoy also concurs. He argues that, unlike Kerala, most states are seeing a rapid decline in COVID-19 cases as they’re supposedly at the edge of obtaining herd immunity by way of exposure to the virus. However, exposure to the virus isn’t a long-term and safe yardstick to get herd immunity.

Herd immunity offers a proportion of the population indirect protection against a disease, supported the immunity thanks to previous exposure or vaccination. However, since the virus is consistently mutating and persons with weak immunity are often re-infected, vaccination offers better protection against SARS-CoV-2. As of July 7, Kerala has administered 1.51 crore doses of COVID-19 vaccines, covering 43% of the population above 18 years with one dose and only 14% with two doses.

Dr Muilyil does means though, that due to new coronavirus variants like Delta, the herd immunity level we’d like to succeed in has gone up to a touch over 80%. “However, as long because the vaccine coverage picks up, the deathrate shouldn’t rise,” Dr Jayaprakash says.

While within the first wave, the daily cases during the plateau period were between 5,000 and 6,000, this has doubled within the second wave, ranging between 10,000 and 15,000. However, since the state has largely been ready to steadily expand its healthcare requirements, the active cases are yet to place pressure on the health infrastructure within the state. “That is why the plateau isn’t a concerning factor now. It becomes a priority when the critical care units get filled up,” says Dr Arun.

Dr Muliyil says, “It also seems like the healthcare system in Kerala could handle the caseload throughout. the worth of this management is that you simply have a protracted epidemic. My guess is that in Kerala, there aren’t very many repeat infections, but that it’s mostly the new infections that are becoming recorded. they need done an honest job of flattening the curve.”

Meanwhile, experts also caution that it might be a cause for concern if the COVID-19 cases were to spike exponentially. “The pandemic curve is named a plateau when a consistent range of cases are reported for weeks. it’ll remain so for a few weeks, before normally coming down. However, it becomes a drag if there’s a spike in cases before the pandemic curve declines since the cases are high because it is,” acknowledged Dr Sulphi Nooh, a member of the Indian Medical Association (IMA).

Dr Arun notes that the present plateau is probably going to continue for one or two months more. However, he views this plateau as a plus . “If the utmost number of population are often vaccinated during this point , before subsequent spike, it are often beneficial for us,” he says. Health experts also add that conducting seroprevalence surveys — estimating the proportion of the population that has antibodies against coronavirus — at now also can be an efficient method to know the trajectory of the pandemic.

Experts also stress that lockdown restrictions and relaxations should be implemented more scientifically during this era . “If the prevailing perfunctory control continues, it’ll drive Kerala to the state that we witnessed post the Assembly polls when cases began to spike again. In such a situation, cases will return to 30,000-40,000 (as against the typical of 12,000 daily cases now),” says Dr Sulphi.

Many also means that the implementation of basic regulations – like physical distancing, wearing face masks and, more importantly, contact tracing – in Kerala has become weak now.

Meanwhile, during a letter to nine states with high COVID-19 cases — Kerala, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Odisha, Tripura and Sikkim, the Union Health Ministry, on July 7, asked officials to build up testing and vaccination, plan healthcare infrastructure effectively, follow COVID-19-appropriate behaviour and effective clinical management.

cheetah magnificent but fragile experts list concerns for cheetahs

cheetah magnificent but fragile experts list concerns for cheetahs  A historic day for 21st century India PM Modi launched 5g in India

A historic day for 21st century India PM Modi launched 5g in India  EMM Negative rare blood group found in Rajkot man 11th such case worldwide

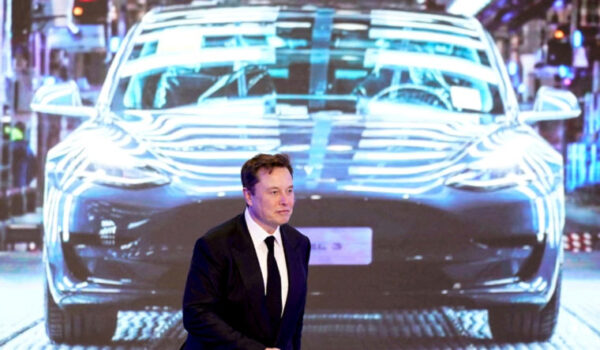

EMM Negative rare blood group found in Rajkot man 11th such case worldwide  political leaders invited elon musk to set up tesla plants in their states

political leaders invited elon musk to set up tesla plants in their states  Gujarat Vidyapeeth by mahatma Gandhi in 1920 will invite governor acharya Devvrat

Gujarat Vidyapeeth by mahatma Gandhi in 1920 will invite governor acharya Devvrat  In Daring Op, Air Force Pilots Use Night Vision Goggles To Land In Sudan

In Daring Op, Air Force Pilots Use Night Vision Goggles To Land In Sudan